Wataru Yoshida had had enough. He wasn’t going back to school.

He disliked his teachers, chafed against the rules and was bored by his classes. So in the middle of 2020, as Japan’s schools reopened after pandemic closings, Wataru decided to stay home and play video games all day.

“He just declared, ‘I’m getting nothing from school,’” said his mother, Kae Yoshida.

Now, after more than a year out of the classroom, Wataru, 16, has returned to school, though not a normal one. He and around two dozen teenagers like him are part of the inaugural class of Japan’s first e-sports high school, a private institution in Tokyo that opened last year.

The academy, which mixes traditional class work with hours of intensive video game training, was founded with the intention of feeding the growing global demand for professional gamers. But educators believe they have stumbled onto something more valuable: a model for getting students like Wataru back in school.

“School refusal” — chronic absenteeism often linked to anxiety or bullying — has been a preoccupation in Japan since the early 1990s, when educators first noticed that more than one percent of elementary and middle school students had effectively dropped out. The number has since more than doubled.

Other countries like the United States have reported higher rates, but it is difficult to make direct comparisons because of varying definitions of absenteeism.

Japanese schools can feel like hostile environments for children who don’t fit in. Pressure to conform — from teachers and peers alike — is high. In extreme cases, schools have demanded that children dye their naturally brown hair black to match other pupils’, or dictated the color of their underwear.

Making matters worse, counselors, social workers and psychologists are rare in schools, said Keiko Nakamura, an associate professor of psychology at Tohoku Fukushi University. Teachers are expected to perform those roles in addition to their other duties.

As they struggle to address school refusal, educators have experimented with different models, including distance learning. In December, Tokyo announced that it would open a school in the metaverse. Promotional photos looked as if they were straight out of a Japanese role-playing game.

Frustrated parents with means have turned to private schools, including so-called free schools that emphasize socialization and encourage children to create their own course of study. The E-Sports High School students, however, mostly found their own way to the school.

More on U.S. Schools and Education

For them, it seemed like a potential haven. But for their parents, it was a last resort. Once the school realized it was tapping into an unexpected demographic of absentee students, it invested considerable effort in soothing parental concerns.

At an information session in February 2022, a PowerPoint presentation explained that the school’s lesson plans met national educational standards, and administrators addressed concerns like video game addiction and career prospects for professional gamers.

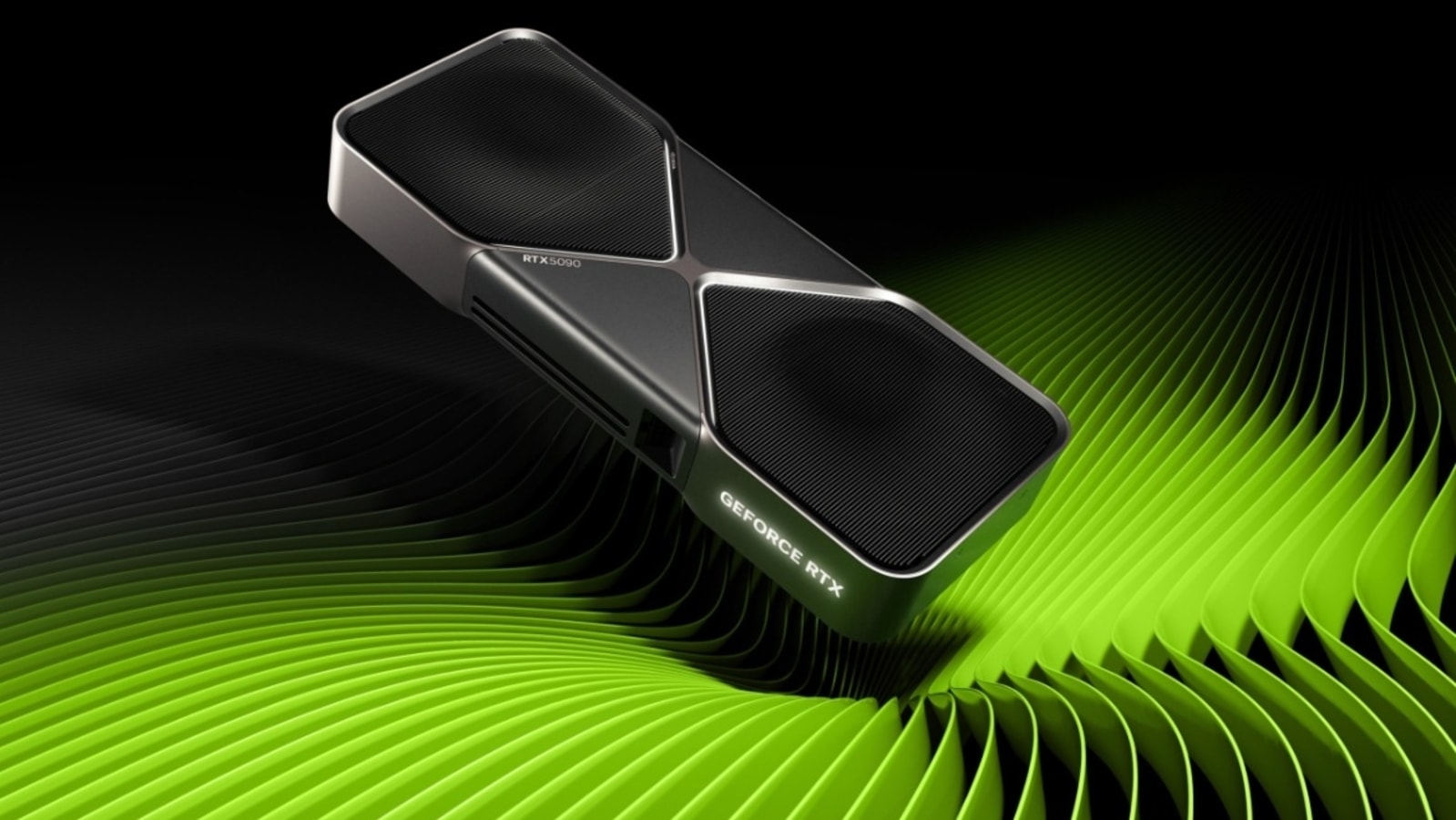

Two months later, at the start of the Japanese school year in April, 22 boys, accompanied by dark-suited parents and grandparents, gathered for an entrance ceremony at the school’s gaming campus. It is a sleek pod — half spaceship, half motherboard, with glass floors and a ceiling circuited with green neon tubes — on the eighth floor of a building in the bustling Shibuya district.

The ceremony offered reassurance to both students and parents. A former minister of education sent a congratulatory telegram on the school’s opening. The principal — in the form of a glitchy virtual avatar — delivered a speech from a giant screen, then led students in a programming exercise.

That mix would continue throughout the school year. On Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays, pros instructed students on competition strategies for popular games like Fortnite and Valorant. On one such day, students gathered around a whiteboard for a nearly scientific lecture about the relative merits of Street Fighter characters, then broke into groups to put the lesson into action.

On Tuesdays and Thursdays, students studied core subjects like math, biology and English. Unlike at normal Japanese schools, classes started later, at 10, and there were no uniforms.

Another unaccustomed sight for a school in Japan: tardiness.

On one day early in the school year, only two of the boys showed up for the start of first period, a lecture about information technology. There were four teachers.

As pupils straggled in, the teachers offered a cheery hello or simply ignored them. By third period — biology — five students had arrived. Only two stayed through the day’s last class, English.

The teachers were happy they came at all.

“Kids who didn’t come to school in the first place are allergic to being forced,” said Akira Saito, the school’s principal, an affable bear of a man who had spent years teaching troubled students in Japanese public schools.

The academy’s philosophy was to draw them in with the games and then show them that “it’s really fun to come to school, it’s really useful for your future,” he said.

Torahito Tsutsumi, 17, had left school after bullying drove him into a deep depression. He spent all day in his room reading comics and playing video games. When his mother, Ai, confronted him about it, he told her that his life was “meaningless.”

“When other parents told me their kids weren’t going to school, I thought, ‘You’re spoiling them,’” she said.

It was a typical response. Traditional Japanese education puts a premium on cultivating grit — known as gaman. Educational methods often focus on teaching children the value of endurance, dispensing harsh punishments and avoiding anything that looked like coddling.

But as Ms. Tsutsumi watched her son sink into depression, she feared what might happen if she tried to force him back to class. She had begun to lose hope when Torahito saw a television ad for the e-sports school.

She wasn’t sure whether it was a good idea, but “the most important part was that he wanted to attend,” she said.

By the school year’s halfway point, Torahito had made progress. He arrived at school every day promptly at 10 and had become more optimistic, his mother said. But he hadn’t made as many friends as he’d hoped, and he didn’t think he was competitive with the other gamers. He wanted to work in the video game industry, but wasn’t sure how he could.

In truth, few of the students will become pro gamers. E-sports have never caught on in Japan, where people prefer single-player games. And careers are short anyway: Teenagers — with their fast-twitch reflexes — dominate. By their mid-20s, most players are no longer competitive.

The academy’s teachers encourage students to seek other paths into the industry — programming or design, for example — and to make pro gaming a sideline, not a career.

Wataru, however, is focused on making it big. By midsemester, he still wasn’t getting to class much, but overall he was thriving, commuting over an hour, three days a week, for practice. He was less reserved, more eager to goof off with his new friends.

The tournament was remote, but on the day of the second round, Wataru and his teammates showed up at the gaming campus early. The room was empty except for a few chaperones. One team member had overslept and would play from home.

They won their first game. Then a group of older players smashed them.

Defeated, the team’s members sat quietly for a time, the light from the monitors washing over their disappointed faces.

“I should probably go home,” Wataru said.

He turned back to his monitor instead. He was part of a team. And he was getting better at that, too.